New year, same annual attempt to revive this newsletter from the deep recesses of my psyche, where thoughts languish unexpressed until they erupt from my brain and into your inbox. I ended 2023 on a cinema bender and kicked it off with a resolution to read (or listen to) at least one book per week, which I’m finding easier than usual thanks to the hour-and-a-half I spend idling in traffic on any given day. Already I have trudged through books about waif-like prison secretaries and lesbian Brooklynites and gut-wrenching, star-crossed love and I am making a concerted, if historically unsuccessful, effort to log said books on Goodreads. Without further ado, here are some recent faves, let-downs, and up-and-comers on my culture radar for 2024.

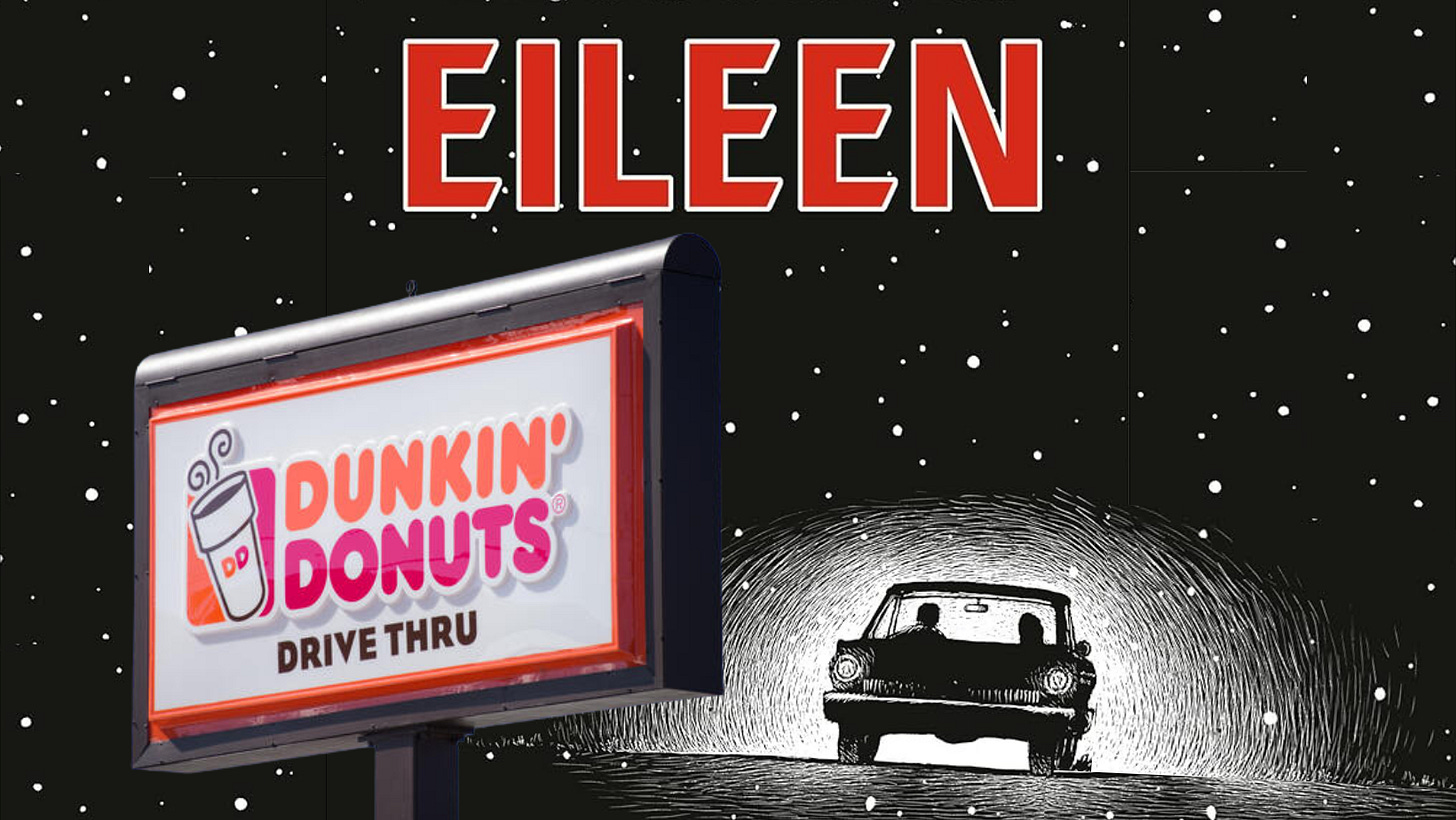

Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh

“Plain face” this. “Small boobs” that. What I really want to know is why Moshfegh, a Boston native, fails to indicate the presence of a Dunkin’ Donuts in X-ville. Eileen is set in 1964. Dunkin’ was founded in 1950. Does she expect me to believe that after waking up hungover in the driver’s seat of her car, door open, crashed into a snowbank and sitting beside a frozen pool of her own vomit, Eileen does not calmly close the door, pull out of the snow bank, and drive to the nearest Dunkin’ for a large hot coffee, regular?* Obscene.

*Regular [reg-yuh-ler] adjective; origin, Boston; Coffee with cream and sugar.

The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi

Akwaeke Emezi is number one on my list of authors who could scribble nonsense on a bar napkin and I’d read it with enthusiasm. In The Death of Vivek Oji, released in 2020, they spin a tale of love, family, and self-acceptance in the aftermath of a tragedy. Young Vivek is already dead when we meet him, but his ghost lives on in the memory of her parents, friends, and cousin/lover Osita, all of whom struggle to make sense of Vivek’s unapologetic queerness in the midst of the social upheaval of Southeastern Nigeria in the 1990s. There are few things I find more moving in literature than the delicate texture of grief. Vivek’s loved ones fall into one another as they fall apart. They nurse and tear open their wounds, asking questions that cannot (or will not) be answered as they hunt for a way out of the hurt that surrounds them.

Dykette by Jenny Fran Davis

Nursing corsets. Nude Grinch selfies. Non-dairy milks. Davis addresses these and other pressing issues in her debut adult novel, Dykette, a comedy of errors in which a lesbian couples retreat devolves into a Femme-vs-Femme smackdown in the wilderness of *checks notes* upstate New York.

High-femme writer Sasha and her set-designer girlfriend, Jesse, are spending the holidays with their queer elders, Jules and Miranda, at the older couple’s renovated farmhouse. They are joined by Jesse’s best friend, Lou, and Lou’s girlfriend, Darcy, a beautiful artist who, to Sasha’s chagrin, is collaborating with Jessie on a performance art piece to be live-streamed later that week. What follows is a contest of wandering eyes: Jesse has eyes for Darcy and Jules has eyes for Sasha and Sasha has eyes for Jesse and for Jules, but what she really wants is everyone’s eyes on her. She seethes with jealousy as the group thrifts, hosts themed dinners, and screens Boys Don’t Cry. These are just a few examples of the queer tongue-in-cheek that made me give up on the novel two times in the two years since I was offered an uncorrected manuscript. I was so young then, one small fish in a sea of eager, naive booksellers sought out by Holt for the same, damning crime: a positive staff review of Detransition, Baby.

Dykette is less fiction than it is thinly-veiled memoir, with entire passages lifted from the author’s controversial 2020 essay “High Femme Camp Antics.” A cursory scroll through Davis’s Instagram is as good an introduction to the characters and premise as is the novel itself. (“Wait. Is this fucking [book] about us?” reads one riff on the viral Euphoria meme.) All this might be forgiven if not for the reductiveness of the writing, an undeniable consequence of the influence of Maggie Nelson on a very specific echelon of white, university-educated lesbian writers who haunt the New York City lit scene. But autotheory is a poor substitute for plot, and Davis’s nods to Leslie Feinberg, Carmen Maria Machado, and Nelson herself read more like an application to join the queer canon these authors comprise than they do a sincere effort to contextualize the story she has written. Setting its thesis-length theory of white queer femininity aside, Dykette does best when it eschews aesthetics and stereotypes in favor of the practical, and in its climax, the grotesque.

If you are committed to reading this book, a choice I can’t in good faith endorse for anyone not (1) a lesbian who (2) likes to complain about things, you’ll find that the most interesting question Davis asks is simple: As the battle of the Dykettes rages on, how far is Sasha willing to go to come out on top?

At the Movies

I considered writing about my ambivalence to the discourse surrounding Greta Gerwig and Margot Robbie’s Oscar “snubs” for Barbie, but Whoopi Goldberg said it best: “[A snub] assumes someone else shouldn’t be in there… Not everybody gets a prize.”

Instead, might I suggest that we collectively turn our attention to recent films starring or written or directed by women that didn’t net millions of viewers and a billion dollars to boot? For example, you might watch Celine Song’s Past Lives, a film about a dormant, rekindled romance starring the blessedly tender Greta Lee, or the dramedy Fremont*, in which first-time actress Anaita Wali Zada stuns as an Afghan refugee and former translator working in a San Francisco fortune cookie factory.

You might bask in the light of Da’Vine Joy Randolph’s masterful performance as grieving cafeteria chef Mary Lamb in The Holdovers, my favorite movie of the season and further evidence of my previously stated belief that more art should be set in Western Massachusetts. Randolph built her role from the ground up. She learned to smoke cigarettes by the pack and selected her characters’ costumes. She affected a distinct Boston accent, the rarely if ever acknowledged lilt specific to Black women in the city in the early ‘70s. Hers is the stand-out performance in a universally well-acted and beautifully written film.

You might find that Lily Gladstone gives a tour de force performance in Killers of the Flower Moon and Emma Stone is brilliant in Poor Things and Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman (and Charles Melton, justice for HIS Oscar snub!) are devastating in screenwriter Samy Burch’s May December. And when the drama proves too heavy, you might laugh out loud at Ayo Edebiri and Rachel Sennott’s turn as lesbian losers in Emma Seligman’s camp comedy Bottoms. This is just a handful of recent movies made by or starring women that I have personally seen, each of which is acclaimed in its own right. There are a great many more that I haven’t.

You might, the next time you’re feeling some type of way about the representation of women onscreen or at the Oscars, consider giving one of these films a few hours of your time.

*Content Warning: Jeremy Allen White.

Up & On Deck

I braved rush hour traffic and limited parking to see Hanif Abdurraqib read from his forthcoming book There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension at Northeastern earlier this week, and god am I excited for its pub date in March.

This week I’m watching Anatomy of a Fall , cracking open my copy of the late Anthony Veasna So’s Songs on Endless Repeat, and listening to the sweet, sweet sound of Tom Hanks narrating Ann Patchett’s The Dutch House.

Thanks for reading, and see you soon <3

adore this so hard

-griffin